When human beings,

or even dinosaurs, fail to deliver consolation in times of doubt, uncertainty,

and maybe even a little despair, there are always libraries.

For instance …

This afternoon, I

needed to get out of the house. It’s been a bad week, in some ways. Not so bad

in others. One part of me wanted to just sit at home, lie on the bed, and

contemplate my misfortune. Luckily, I recognized that doing so never solved

anything. I have a lot of work to do – work that I want to avoid, and still

have to some degree.

And, of course, I

have writing to do as well, which I don’t want to avoid, but I had a hard time

working myself to get any done. I’m in the dumps.

My fall class at

Columbia was canceled.

And this time, I

can’t really blame the administration, the department, or anyone but the

students. They just didn’t sign up.

Not enough of

them. Just nine, I think. And I thank those nine for signing up. And I also

apologize that now there won’t be a course for them to take.

But when you get

ready to put on a show, so to speak, and no one comes, you can’t help feeling

bad. Feeling like a failure. Or an outcast. I have some experience in feeling

like an outcast.

And when you feel

like an outcast, it’s very difficult to motivate yourself to soldier on and

produce new work. Even if you’ve had some relative success, all you can

remember are the failures, the empty rooms, the silence.

So, sitting in

the library, I started writing, then looked around. Who needs any more stories?

I’m surrounded by five thousand books. Who needs to read anything by me? What

the hell do I know? I think science fiction will not only save literature, but

maybe save the world. How dumb can you get? If readers don’t want Tiptree,

Delany, Sturgeon, Lafferty, on and on and on, who the hell wants me?

Well, this is no

good, I thought. I got up and started checking out the shelves, looking for

something to read to remind me what good words look like when put together.

Good sentences. Good storytelling. I also wanted to see what books I have loved

are still hogging shelf space. On previous scans of the shelves, I’d discovered

a number of my favorites had been “disappeared” to make more space. Catalog

searches proved they were gone. Kaput. Outta here.

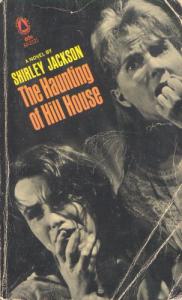

But I did find

this: The Haunting of Hill House, by

Shirley Jackson.

Memory is the

ultimate censor, but if I recall correctly, Jackson’s novel was the first “grownup”

novel I read, excluding books by Wells and Stevenson, which some considered “kid

stuff” (the Wells novels were in editions specifically marketed to children).

I had also

included the novel in a list of books that made a great impression on me or

were favorites. I had read Hill House

in many years. I retained my very first copy of it in my library, but handle it

with care, afraid it might turn to dust if I finger through it too rapidly.

Did it still

retain its power?

I took the

edition off the shelf, flipped it open, and started reading at a random page.

It’s early in the novel: Eleanor’s car trip to Hill House. It’s a section that

fascinated me when I first read it as a kid and which still fascinates me. You

would think a boy, especially a boy living in Chicago, in Garfield Ridge – a place

of mediocre little schools and mean-spirited, mediocre little minds, a paradise

for the venal and the superficial – would be bored by all this. “Come on! Let’s

get to the house! Let’s get to all

the haunted stuff!”

But no. I didn’t

know who Eleanor was, but somehow I detected a kindred spirit in her. She didn’t

feel at home at home. She is

wandering, heading off to Hill House, daydreaming along the way.

She stops at a “country

restaurant” and notices the family at another table, the only other customers

at that time of day: parents, a young boy and a little girl.

…

The light from the stream below touched the ceiling and the polished tables and

glanced along the little girl’s curls, and the little girl’s mother said

calmly, “She wants her cup of stars.”

Indeed,

yes, Eleanor thought; indeed, so do I; a cup of stars, of course.

“Her

little cup,” the mother was explaining, smiling apologetically at the waitress,

who was thunderstruck at the thought that the mill’s good country milk was not

rich enough for the little girl. “It has stars in the bottom, and she always

drinks her milk from it at home. She calls it her cup of stars because she can

see the stars while she drinks her milk.” The waitress nodded, unconvinced, and

the mother told the little girl, “You’ll have your milk from your cup of stars

tonight when we get home. But just for now, just to be a very good little girl,

will you take a little milk from the glass?”

Don’t

do it, Eleanor told the little girl; insist on your cup of stars; once they

have trapped you into being like everyone else you will never see your cup of

stars again; don’t do it; and the little girl glanced at her, and smiled a

little subtle, dimpling, wholly comprehending smile, and shook her head

stubbornly at the glass. Brave girl, Eleanor thought; wise, brave girl.

“You’re

spoiling her,” the father said. “She ought not to be allowed these whims.”

“Just

this once,” the mother said. She put down the glass of milk and touched the

little girl gently on the hand. “Eat your ice cream,” she said.

When

they left, the little girl waved good-by to Eleanor, and Eleanor waved back,

sitting in joyful loneliness to finish her coffee while the gray stream tumbled

along below her. …

This is an

incredible moment that a lesser author would have probably cut in an early

draft – “No, let’s get to the action. Let’s not dawdle.” Or an editor would

have made the same suggestion. “No one wants to read about country restaurants!

Hell, let’s get this show on the road!”

But the show is on the road. The show is Eleanor. And

in this little moment we get the answer to the question I keep asking students

and fellow writers when I read their work, and so often – so very, very often –

they cannot answer with even faint success: “Why the hell should I care what

happens to this person?”

Eleanor wants her

cup of stars.

We all want our cup of stars.

Eleanor knows.

She was trapped into being like everyone else, at least on the outside. You

concede your cup of stars and for the rest of your life you struggle to get it

back. Eleanor and the little girl exchange this wisdom silently, and it is not simply

Eleanor imparting wisdom to the little girl – she isn’t. The little girl is

imparting as much to Eleanor as Eleanor is warning the little girl.

I don’t pretend

to know what great literature is. I believe, perhaps wrongly, that I know good

storytelling, and good writing, and how to bring a notion across to its most

powerful effect. And this is certainly great storytelling, great writing – a brief

moment, a stop on the road to destiny that tells us almost everything we need

to know about Eleanor while revealing a startling awareness of our own secret

dreams.

There’s a lot of

talk these days, especially among folks of my generation, about whether books

we read when we were young “stand up” today. Maybe they have a point, because a

lot of what they read (me too) was a lot of crap. Earnest crap. Exciting crap.

But … crap.

But then I think:

stand up? To whom? Who has appointed

these arthritic bozos the Grand Jury of Literature? They were stupid enough to

read and love the crap in their youth. I should take their judgments seriously now?

Perhaps it makes

one feel cool and wise now to eviscerate the giants of our youth, to call “Fraud!”

and “Foul!” on former heroes. Perhaps that’s an exercise everyone needs to

perform to understand how the world changes and how we change within that

world.

But perhaps a few

moments should be spent not in judging how the works we read in youth stand up

for us, but how well we stand up against the works we read.

Have we kept our

cup of stars?

I went back to my

reading table and scribbled out a few more pages of words, most of which I will

probably cross out and try to come up with better ones, reminding myself of

something I’ve been telling myself a lot: All

great stories are love stories. All great stories are about loneliness. These

two sentences are not mutually exclusive.

Writing is never

easy, but the only way you get it done is to keep going through the tangle of

uncertainty and fear and emptiness. Take a break, enjoy your coffee, but at the

end of road, Hill House awaits.