One

of my former students recently posted on his Facebook update: “Advertising/marketing

is the art of mind control. It creates the illusion of choice where there is

none.”

Well, one can dicker. “Manipulation” over “control,” maybe. “Suggestion”

might be substituted – especially by those who work in the industry. Or “increase

visibility.” Then there’s “con game,” “scam,” “flim-flam,” “misrepresentation” …

These terms can be thrown around – and they are. It’s been some years since I

took advertising classes. Yes, I did. And guess what? I got A-plus all the way

through. When my advertising instructor at Northwestern heard I was planning to

get a degree in English, he looked at me as if I had just set fire to a

Dumpster loaded with money.

The words that come to mind, though, when I think of some aspects of

advertising and marketing (some

aspects – hey, I know people who work in the field, I save my broad brushes for

the folks in politics) are “condition” and “train.”

Yeah. “Training.” We hear about training all the time these days. Training is

good, right? Training is supposed to

be what we’re doing in the schools.

Advertising and marketing people, since the days of Edward Bernays, have

been training consumers (by their labels ye shall know them) to, well … to consume.

And they’ve been doing a damn fine job of it, don’t you think? Americans

can consume like nobody’s business (and the business of America, after all, is business). We have built mighty

cathedrals of consumption, on the ground and in the air – out of brick and out

of electrons. Math skills, science skills, language skills, thinking skills –

hey, who needs that? Only insofar as they permit us to make more money to

consume more stuff.

Oh, yeah – there’s the problem. Consumption needs fuel, and the fuel is money,

and recently, outside of a narrow, narrow margin of our more affluent citizens, we

don’t have as much scratch to go consuming with anymore.

Fear not: somewhere, brainy people are being grossly underpaid to work out

the problem of how to get millions of people to consume more without paying

them more, if not by paying them even less. There’s gotta be an algorithm for

that.

If you’re old enough to remember the old Mentor Books’ series on the

history of Philosophy, you’ll remember we had an Age of Belief, an Age of

Adventure, an Age of Reason, an Age of Ideology and, bringing up the rear of

the twentieth century, an Age of Analysis (by thy labels ye shall know them).

Well, simpler minds at simpler tasks have managed to cast our current world

as an Information Age.

So, what do you do in an Information Age?

You gather information. And gather information. And gather more

information, to gather even more

information. Our answer to everything is to gather more information. The

culture has become an intellectual one-trick pony.

Powerful people are spending countless dollars trying to gather information

on what you consume in order to get you to consume more of it.

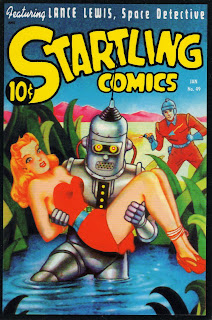

So why the hell do I care? I’m just a writer. An impoverished writer, who

don’t know nothing about no things no way, right? I just write about flashy ray

guns and flying cars and starships and giant battling robots.

I don’t care. There are plenty of social commentators and critics who’ve

got all of this down solid. They can write this whole tirade five days a week, fifty

weeks a year. The same damn critique, over and over and over.

And some of them do.

So, why is this under my skin at the moment?

Remember that kid in my story, the one I quoted from in the last post? Val?

She sounds furious. Passionately furious.

And part of my job as a science fiction writer is to depict what she’s furious

about – to try to capture it in an instant or two, and to do it without too

much coaching from the sidelines by the author/narrative voice.

I do so – mostly miserably, at least at first. I hammer and hammer away at

the scene until I think I’ve got it as good as I can possibly make it, which I

know is probably not good enough.

Before that impassioned scream, that barbaric yawp Valerie made in that

French bakery, I wrote a scene inspired by something I noticed in Union Station

back in the summer, while I was waiting for a friend who was crossing the

country by Amtrak.

I waited, and I heard this strange chattering in my ear. It sounded like a

hundred manufactured “human” voices – versions of the same voice – all speaking

at once.

They were coming from each of the platform entrances. It was an aid for the

visually impaired: a voice, electronically neutral-sounding, tells you what

platform you’re standing in front of. I assume the visually impaired person’s hearing

ability is keen enough to distinguish Platform Twelve from Platform Fourteen,

but to me it sounded like a hive of indistinguishable voices, all going at once

– this audio-ocean of words and numbers repeated endlessly.

My first thought was that it sounded like a sound installation from a

clever conceptual artist.

My second thought was that this is sort of what it sounds like now,

everwhere, all the time. And that in the future it will sound like this, but

louder. And the voices won’t be coming from the speakers over the platforms in

Union Station, but they’ll be inside our heads.

On the train home I wrote this scene, where Charlotte Weber, the story’s

protagonist, takes the escalator up to the mezzanine, where the Water Tower

Place atrium space begins:

As Charlotte rode the escalators to the mezzanine, a wall of

giant screen advertisements greeted (or assailed) her, each one with a

well-dressed, physically “perfect” spokesperson, coiffed and made up with

painstaking (or painful) artistry, and each one with a professionally-modulated

voice, speaking from scripts that teams of “content specialists” (there were no

writers anymore) slaved upon for months, telling her the wondrous benefits of

some company’s product or service – or whatever it was they were trying to

sell. Charlotte couldn’t tell. No one could tell. All the faces, all the

voices, tried for the same sincerity, the same directness, the same familiarity

– as if these professional strangers had known her for years. All the voices on

all the screens blended into an empty cacophony and no one message could be

heard over another.

Not that it made a difference.

And not that it was any better on the mezzanine. Every shop,

every boutique, sported big screens, 3-D and holograms of unnaturally “real”

people looking straight at you as they told you what great things to buy.

And so it was on Level Three. And Level Four. All the way up to

Level Seven. A hundred shops with a hundred displays that spoke intimately,

plaintively, admonishingly to you –

– But never saw you – could never see you.

And that was the way of the world, if you occupied a place high

enough in the social scale, in that country, at that time.

Once, if you heard a hundred voices in your head, calling to

you, it was conventional practice to seek out help, counseling, medication. In

another age, it may have meant you were a prophetess, or were possessed. Now,

if you heard all those voices, all it meant was that you were shopping, in real

or virtual space.

The only voice Charlotte had trouble hearing was her own.

Is

it accurate? Does it reflect the world Charlotte occupies, and does her world

reflect our own? I honestly don’t know.

This

is what I’ve come up with and until I can come up with something better it will

have to stand.

All

I can say is, later on in this story, Charlotte and her friends visit a little

shop on Level Six, a place that sells these little bioengineered “toys,” shaped

like dinosaurs, who are supposed to smile and greet you and sing, “Yar-wooo!

Yar-woooo!”

Except

for the gray, grimacing stegosaur who says, “G’wan! Beat it! Scram! Smelly

humans! Keep your hands to yourself!”

It’s

not a ray gun. It’s not a flying car. It’s not a starship. It’s not a giant,

battling robot.

But

it’s what I work with.

“What should young people do with their lives today? Many

things, obviously. But the most daring thing is to create stable communities in

which the terrible disease of loneliness can be cured.”

- Kurt Vonnegut

No comments:

Post a Comment