At the risk of infuriating my students and

colleagues yet again, and doing so in the shadow of the recent, tragic fire at

the Cathedral of Notre Dame, I've been thinking recently about the similarities

between stories and cathedrals, and maybe how the one helps to explain the other,

at least to some degree.

I often refer to stories having “shapes.”

I learned the phrase “story-shaped idea” from somewhere and it has never left

me. I have had numerous problems with discussions of story structure as

practiced in academic and non-academic circles. I learned only recently what a

“Freytag Triangle” (or “Pyramid”) is,

and it turns out to be the renaming of a description for “story” I've

encountered most of my life, and found true only in the most general (and least

helpful) sense.

The Freytag Triangle. Writers

fly into it and are never seen again.

Three-Act Structure. For the

geometrically-impaired.

Six-Act Structure. Three-Act

structure cut into smaller pieces.

Plotto. Pick a plot – any plot.

The Lester Dent Master Plot. Pick this plot!

The Hero’s Journey. A train that only travels in circles.

Narratology – Don’t

Go There!

Seriously, all these terms surrounding

narrative structure are all fine and well (when I'm in a good mood), but they

are at best what you might call “analytic.” Some of them apply best to

completed works but do little to help the author of a work in progress. Some of

them will help an author construct a plot, but a plot is not a story.

I return to the brilliant observation

of book editor Teresa Nielsen-Hayden: “Plot is a literary convention. Story is

a force of nature.”

Narratives or plots may be “structured,”

but stories are shapes, like containers, or vessels.

On a practical level, they must

perform a function and contain the elements essential to make the comprehensible

and meaningful communication we tend to call a story.

On an aesthetic level, the variations

of shapes, colors, materials and the like are limitless. Function may dictate

form, but both form and function are determined by that natural force: Story.

We may not know what it is, but we

recognize it when we see it.

More or less.

Sometimes function hides in form, but

it is certainly there.

Sometimes the form proclaims the

function loudly.

Story can’t survive without a

structure, and a structure without a story has no purpose.

The same, to some degree, can be said

for cathedrals.

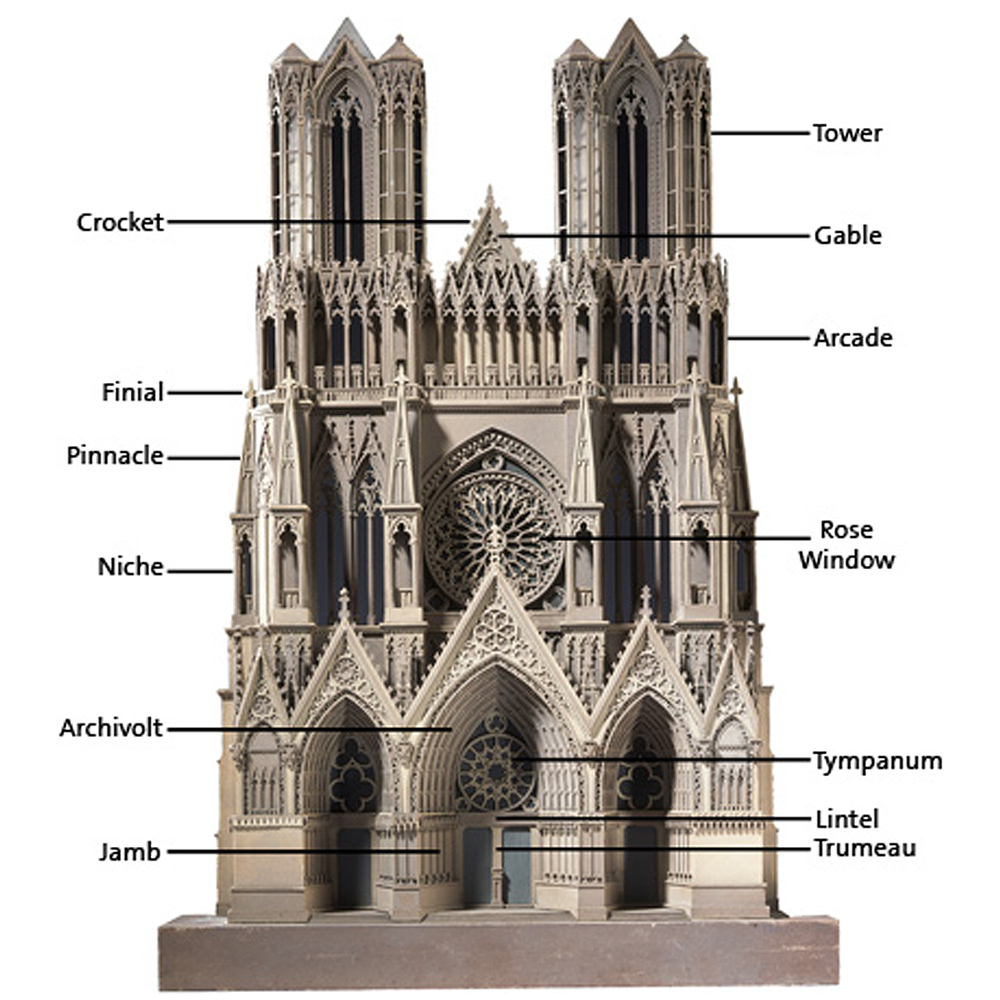

They have elements that help define

them as cathedrals: narthex, nave, transept, choir, ambulatory, towers, gables,

pinnacle, niche, tympanum, rose window … and so on. Other structures may

contain these elements, but are not cathedrals, but nearly all cathedrals will

contain these elements – and something more.

At the heart of a story is a point.

It may not be a “big” point, or a good point, and it may not be one consciously

conceived by its author, but if you look at the story long enough, you’ll find

it. One may argue that it is there only because you’ve searched for it, and

it’s the product of your searching more than it is of the author’s intention,

but it doesn’t matter. Stories are for readers, an audience, and this is one of

the things readers do with what they read – again, whether it was their primary

intention or not. We read stories for many reasons, and some of those reasons

we’re not conscious of at first, or even later, or ever.

At the heart of every cathedral,

likewise, is a point. It is a manifestation of a view of the universe, of

metaphysics, of theology.

It is a model of the universe as conceived

by its initial adherents, perhaps, but it is more than a treatise written in

stone, wood, and glass. And one doesn’t have to be an adherent to the

worldview, or metaphysics, or theology, to appreciate the point the building

makes.

It is a design, but it is not the

product of any single designer (except for more recent examples); it is the

product of many, laborers, craftspeople, artisans.

Each cathedral built along the

general principles outlined by what we recognize as common or defining elements

to the structure, but each one is distinct, different – its own experience. And

every individual who journeys into the structure will find something distinct

and, possibly, wondrous within it (and around it), beyond the intended tenets

of any specific religion, spirituality, or theology.

And this is one reason why we are

often moved so deeply when we visit these places. They are singular structures,

but their very singular-ness is an

echo of an entire reality – not to be mistaken for “reality” itself, whatever

that is, but a response to reality, one of many within the human experience.

Which also can be said, without too

great an exaggeration, of a story. The materials differ (thank heavens for

that; fiction is cheaper and easier to carry around), but the results,

potentially, are often the same.

Neither cathedrals nor stories should

ever be taken for granted.

No comments:

Post a Comment